“We had to save both.”

As Sarah Custer gasped for air in the back of a van on U.S. 127, all she could think about were her children — especially the one inside her. If Sarah couldn’t breathe, neither could Isabel.

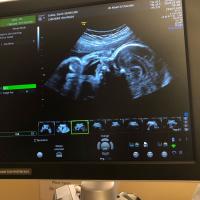

The Custers learned they were expecting baby Isabel just four months earlier, when Sarah was 18 weeks pregnant. Had the surprises stopped there, the Custer clan would’ve grown to a family of five with little fanfare outside of their immediate loved ones. They’d have continued their quaint life in Columbia, a small town in south-central Kentucky.

But recently, life had dealt the young couple one daunting turn after another.

On this October night, as they rushed back to UK HealthCare where Sarah was hospitalized just a couple weeks earlier, each of the 31-year-old’s belabored breaths gave Isabel a chance.

“When I was put under, she was still in my tummy,” Sarah said of that night in 2021. “When I woke up, I didn’t have a baby (inside me) anymore.”

Sarah’s road to UK HealthCare

Sarah’s trouble breathing began in August 2021, two months after learning Isabel was on the way.

In early August, the Custers contracted COVID-19. After a couple of weeks, husband Dave’s cough subsided, but Sarah’s lasted into September and worsened. A clinic near their home diagnosed her with mild pneumonia; by month’s end, blood and vomit accompanied her coughs.

The clinic this time, concerned that Sarah might have a clot in her lungs, urged her to go to the nearest hospital. Sarah’s midwife, who was to attend Isabel’s birth at home, recommended the Custers travel to Lexington instead. If Sarah did have a blood clot, she felt it might be necessary to deliver Isabel by C-section at 28 weeks, and “‘You need to be at the best NICU in the state, which is UK,’” Sarah recalled.

Events led them first to Baptist Health Lexington, where scans showed no signs of a blood clot but something more concerning: a large soft-tissue mass blocking both airways in Sarah’s lungs.

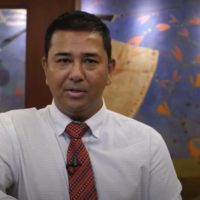

Due to the growing complexity of her case, Sarah was transferred to UK HealthCare, where Dr. Ashish Maskey, director of bronchoscopy and interventional pulmonary, suspected a cancer diagnosis — likely stage 4.

“I can’t describe to you the volume that this thought echoed through my mind — ‘Dear God, why me?’” Sarah said. “My second thought was, ‘Well what are we going to do now?’ And third, ‘What are my husband and children going to do without me?’ That became the leading fear in my head.”

Dr. Maskey’s sense of urgency in developing a plan prioritizing both Sarah’s and Isabel’s needs gave the Custers hope. Before deciding how to proceed, he needed to biopsy the mass in Sarah’s lungs and place a stent to improve her breathing. That called for a bronchoscopy, a typically routine surgery. However, this one would be difficult given the circumstances, as fluctuations in oxygen level during the procedure could have harmed both Sarah and baby Isabel. So, Sarah had to be placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO — a heart-lung machine representing the most advanced form of life support. Cardiologists Dr. Rajasekhar Malyala and Dr. Jonathan Steyn oversaw the ECMO circuit as Dr. Maskey performed the bronchoscopy; Dr. Sumit Dang and Dr. John O’Brien – both specialists in high-risk pregnancies – monitored Isabel’s vitals throughout.

Everything went smoothly. After a few days, Sarah was off ECMO, breathing easier and considering options to treat her cancer while prioritizing her unborn daughter’s safety. Radiation was a non-starter — she feared how it would affect Isabel — and the information they’d received about other conventional treatments wasn’t encouraging.

“You’re not only dealing with life, you’re dealing with quality of life when trying to make that decision,” Dave said. “At what point do you give up and say, ‘It’s not worth going through that for a 20 percent chance at five years,’ you know?”

Difficult conversations

A potential best option remained: Sarah’s biopsy was checked for genetic markers that could give way to targeted treatment options. But it would be a week or two before those results would be available. The Custers decided to wait it out and form a plan — and to do so from the comfort of home after a week in the hospital. Sarah was stable and her stent was supposed to last for months, well beyond the 34-week target date for a planned C-section.

“We had a chance to process and rest, and really mentally and emotionally deal with what had just happened and what it was going to look like going forward,” Dave said. “And to discuss with my parents and, more importantly, her parents, ‘These are the options and these are the potential consequences of these options. If we choose this route and it doesn’t work, this is where we might end up.’”

When the two met in 2017, they never dreamed they’d be having end-of-life conversations at all, let alone so soon. Cancer biopsies were the furthest thing from their minds as Dave designed and built their home on 17 acres in rural Adair County. The only blood they were used to seeing came from the hogs and chickens they raised for meat. And while metal instruments had been a fixture in their lives — Dave owns a blacksmithing business — scalpels weren’t. Before her stunning cancer diagnosis, Sarah had never stayed in a hospital; now she worried her life might end in one.

After 12 days at home — filled with the most difficult conversations imaginable, but also the love and support of family and a tight-knit community of friends and churchgoers – the Custers felt confident about the path forward.

Then Sarah was gasping for air in the back of a van on U.S. 127.

Return to Lexington

Dave consoled and helped Sarah breathe while her brother drove them to Lexington.

“It literally felt like I was trying to suck my life’s air through a straw that somebody was pinching,” Sarah said. Her breathing returned closer to normal until they hit Danville, where it became necessary to take Sarah to the ER at Ephraim McDowell Regional Medical Center. A care team stabilized her for transport to UK HealthCare.

The mass in Sarah’s lungs had grown well beyond its previous state, dislodging Sarah’s stent and sending her into respiratory failure. Her life and Isabel’s were in jeopardy.

“When I talked to Sarah, she said, ‘Save my baby,’” Dr. Maskey said. “But when she went on the ventilator, her husband said, ‘Save my wife.’ But it’s not a choice. We had to save both.”

Dr. O’Brien delivered Isabel by C-section at 32 weeks before Dr. Maskey placed a new stent in Sarah’s left airway. Additional scans showed the cancer’s rapid spread — to Sarah’s brain, spine and hips. The scans also showed fractured vertebrae in her back, which later required spinal surgery performed by Dr. Rouzbeh Motiei-Langroudi.

Throughout her multiple surgeries, Sarah was intubated – with a tube inserted into her throat to open her airway, and doctors waited about a week to attempt to take the tube out. Soon after she awoke, Sarah met Isabel for the first time — NICU staff allowed Sarah to hold her newborn daughter.

For months, Sarah had fought for countless breaths so that Isabel could take her own. While Sarah expected to lose the battle for her own life, she took comfort in knowing she’d won the one for Isabel’s — even if it meant not getting to be there for most of it.

“My purpose was, ‘Stay healthy, stay breathing, stay alive for Isabel,’ to give her the best possible start,” Sarah said. “…They did not expect me to live, so I decided since I wasn’t going to be there, there was really no point in allowing her to bond with me. There was a lot more sense in letting her bond with Dave. I needed to concentrate on living, if at all possible.”

The dark before the dawn

Sarah was too weak to remain off a ventilator, so she was reintubated shortly after meeting her daughter. It didn’t last long though: a couple days later, while Dave and Sarah’s mother-in-law were briefly away from the hospital, Sarah awoke and forcefully removed her intubation tube. A nurse quickly responded and stabilized her, but the tube was out and unsafe to reinsert.

That would have been OK, except Sarah’s lungs were so full of gunk that her breathing was as bad as it’d ever been — and she wasn’t strong enough to cough it out.

“We entered this phase where she needs to be awake but can’t be,” Dave said.

Around the same time, they received results from Sarah’s initial biopsy. Dr. Ralph Zinner, director of the thoracic oncology program at UK Markey Cancer Center, explained to Dave that Sarah had “an extraordinarily high concentration” of a rare mutation of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), a gene that helps in the development of the gut and nervous system in embryos. About 4 percent of lung cancers test positive for ALK, and of that 4 percent almost all are adenocarcinoma non-small cell lung cancer, as Sarah’s was.

This all meant that, assuming Sarah could begin breathing again without interventional aids, she could start a course of treatment that included alectinib, a targeted cancer drug that blocks the activity of ALK. But that was a big assumption, and eventually Dave had to decide whether to have a tracheostomy performed — it was unsafe for her to be intubated again, and a tracheostomy – a surgical opening into the windpipe to help her breathe – was the route most likely to extend Sarah’s life.

“We’re Christians,” Dave said. “We have something called ‘the blessed hope,’ that when we pass away that’s not the end. There’s something better waiting. And one of the things she discussed with me was, ‘Worst case, I die and go to heaven.’ And I said, ‘That’s not the worst case.’ The worst case is you don’t die and linger for four or five years, and then our kids — who would not remember anything right now — the only thing they remember then is all that pain and suffering. That’s really the worst-case scenario.”

While they were at home between hospital stays, they’d decided together to not prolong pain and suffering. There wasn’t a clear right or wrong call, but it was easier to talk about than it was to make it.

“We had conversations like that that are wild to think about and be in the middle of having. I had conversations with her parents about burial — that’s where we were at. … I’m like, OK, is she gonna wake up in the morning with a hole in her throat and be like, ‘Why did you do this? Just let me go.’ And then if you don’t, there’s not really a whole lot of recourse for, ‘Why didn’t you do that?’ because she’s gone.”

The turnaround

Sarah drifted in and out of consciousness as Dave weighed the tracheostomy. But then — between continued hallucinations, an unfortunate side effect of her medication mix — Sarah started to cough. Loudly and forcefully. What two months earlier had been sounds of distress were now cries of hope.

As her coughs got stronger, so did Sarah.

“I coughed with purpose and energy,” Sarah said. “I think it was an hour before they came to check on me to do the trach, and they did an X-ray. The people who did the X-ray go, ‘Her lungs are clear.’”

Once targeted treatment began, Sarah’s cancer receded as quickly as it had spread. Her pain level lessened, allowing her to quit some of the mind-altering medications. She was able to hold Isabel — this time knowing she’d get to hold her again.

After about a month in the hospital, Sarah was cleared to continue her care from home. On July 29, 2022 — almost a year after the first dire coughs began — Sarah was officially declared cancer-free. As of Mother's Day 2024, she marked 22 months in remission. Dr. Zinner is optimistic about her outlook going forward.

“Her tumors not only shrank, but shrank incredibly rapidly,” Dr. Zinner said. “It just suggests profound efficacy, and we are seeing patients on this drug having no evidence of cancer coming back years and years later.”

Alectinib, sold under the brand name Alecensa, was first approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2015. In late 2017, it gained first-line treatment approval for ALK-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. In April 2024, it gained FDA approval as a first adjuvant treatment.

Its effectiveness in the treatment of cancers like Sarah’s, as observed through ongoing clinical research, has been eye-opening.

“As stuff comes out about this particular treatment, Dr. Zinner shares that with us as well, because studies are being done on it constantly where it is fairly new,” Dave said. “And with this treatment, there’s no real visible side effects.”

The power of collaboration

In June 2021, Sarah Custer was on top of the world. Four months later, she expected to leave it.

Given her positive health history, it’s hard to say with 100 percent certainty what caused Sarah’s lung cancer, or how long she’d even had cancer before it was discovered. But the combination of her immune system getting suppressed by pregnancy and a COVID-19 infection likely caused its progression to accelerate.

“My immune system had been managing for about a year is their assumption, but there’s no way to know for sure,” Sarah said. “But in the event of my having COVID, my body went, ‘OK, this is a bigger threat’ and turned all its attention to COVID. And having defeated that, turned back around and went, ‘Oh crap.’ My body said, ‘OK, we’re not beating that, everybody just abandon ship here.’”

Sarah found a team who believed. More than 100 doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals were involved in Sarah’s care just in the time she spent in Lexington that fall. In the thick of a historic pandemic, they navigated one of the most unique and complex cases imaginable, providing her and Isabel with a level of care that only an academic health system like UK HealthCare can provide. And the clinical trial that ultimately put her cancer in remission was only accessible at a center like Markey, which in 2023 became Kentucky’s first Comprehensive Cancer Center designated by the National Cancer Institute.

“It’s never a one-doctor show, right?” Dr. Maskey said. “Interventional pulmonary was there. Cardiothoracic was there. Anesthesia was there. Neonatology, OB-GYN, orthopedics, radiation oncology, medical oncology. It’s the collaborative work of highly specialized fields of medicine that gave her a second chance at life.

“We can do garden-variety stuff. We can biopsy things. We can diagnose cancer. But all that training that we did is meant for these isolated, rare cases where we really put our skill to work. It is the biggest gratification for us to be able to help somebody and have them do well. That’s why we stay in a big center and try to help as many people as we can.”

Home again

Gathered on the front porch of their home, the Custers lead an idyllic life. Sarah reads a book to her three children before lunch — homemade chicken salad sandwiches — while their young dog Woody begs for his tummy to be scratched. Dave is in his nearby workshop preparing tools to be sold for the Black Friday shopping season, and art — “the fun stuff” — to be displayed at a Christmas convention after that.

Just watching, you’d never know what they’d been through, a testament to their bonds as well as those near and far who came to their aid in a time of great uncertainty. The family who watched their home, kids and business. The church that collected more than a winter’s worth of firewood to fill their stove. Friends who cared for their livestock and delivered meals. Other blacksmiths who offered their money, time and skills to help keep Dave’s business afloat.

“A stream of letters and cards began to pour in from literally all over the country,” Dave said. “Cards from churches and individuals, some people we knew, some we didn’t. People who were customers of Sarah’s dad’s business who knew and remembered Sarah from before we married. … We were just completely overwhelmed with an outpouring of love, kindness, encouragement, prayer and help, by so many people.”

In the aftermath, Sarah has only one regret: that she wasn’t able to dedicate more of herself to bonding with Isabel while trying to recover. Overcoming cancer is one thing — getting mother’s guilt to subside is another.

That sacrifice, though, gave Sarah time to make amends and an opportunity to — someday, when all her kids are older — explain why it was so important for her to breathe, in that moment, for herself.

“But to her face, it will probably be something different,” Sarah said. “It’ll probably be the fact that she was a perfect baby the entire time when I was desperately fighting to breathe. She was calm and cool as a cucumber. According to all of the monitors, she never panicked.

"Her heartbeat was steady as a rock.’”